Charles “The Monk” Sealsfield

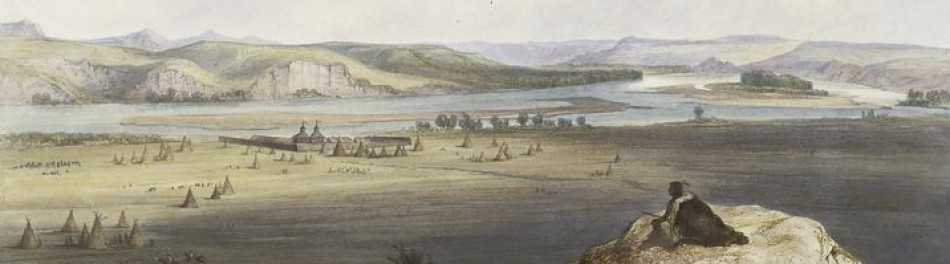

What we know about the life of Carl Anton Postl (1793-1864) could easily be mistaken for the plot of a Gothic novel written by Matthew Lewis or E.T.A. Hoffman: A Moravian monk walks out of his monastery and disappears into the ether — not seen or heard from by friends or family for over 40 years — until it is discovered that he had been living in New Orleans under an assumed name, Charles Sealsfield. He also lived for sometime in both New York and Pennsylvania. A peripatetic spirit, Postl/Sealsfield alternated bouts of writing with extended periods of travel in North America. Born in the village of Poppitz, Moravia, Postl returned to Europe on a number of occasions. There is some speculation that he owned a plantation on the Red River, but there is no definitive evidence to support that. Jeffrey L. Sammons has revealed that for some time in 1830, Postl was associated with a newspaper (Courrier des Etats-Unis) in New York that was owned by Joseph Bonaparte, the former king of Naples and of Spain, then resident in New Jersey!

Charles Sealsfield

Postl, as Sealsfield, wrote over a dozen novels and commentaries/travelogues on North America and Europe. His 1841 novel Das Kajütenbuch (The Cabin Book), depicting Texas as a land of plenty and personal freedom, was immensely popular in both Europe and America in the 19th century. This book, along with others published at the time in a similar vein, helped spur German immigration through the organization of the Adelsverein or German Emigration Company in 1842 — the official title of the organization translated into English was “Society for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas.”

According to Sammons, Sealsfield’s fiction is another iteration of that weird moralistic dichotomy in which “Americans” are pictured as simple and chaste, Anglo-Saxon stalwarts (i.e. men), while people of “darker racial composition” constitute a culture apart. This separate culture (often personified as Indian or Creole women or “The French”) poses a threat to “real” Americans through their “dangerous sensual magnetism.”

A Mason and an admirer of Andrew Jackson’s politics, Sealsfield’s literary output was put to use in Nazi cultural politics. In his “plantation novels,” Sealsfield gives vent to what Sammons, referencing C. Vann Woodward, classifies as a Herrenvolk ideology where slavery provides “the underpinning of a strictly white egalitarianism.” Altogether Sealsfield spent only a few years in North America. Most of his literary output was produced in Europe.

Sources:

Louis E. Brister, “ADELSVEREIN,” Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/ufa01), accessed May 23, 2012. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

Glen E. Lich, “POSTL, CARL ANTON,” Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fpods), accessed May 23, 2012. Published by the Texas State Historical Association

Jeffrey L. Sammons, Ideology, Mimesis, Fantasy: Charles Sealsfield, Friedrich Gerstäcker, Karl May, and Other German Novelists of America (Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 1998).